With the passing this year of Bernard Sayers, aviculture has taken leave of one of the last representatives of its Golden Age. ALAN GIBBARD looks back on Bernard’s remarkable life

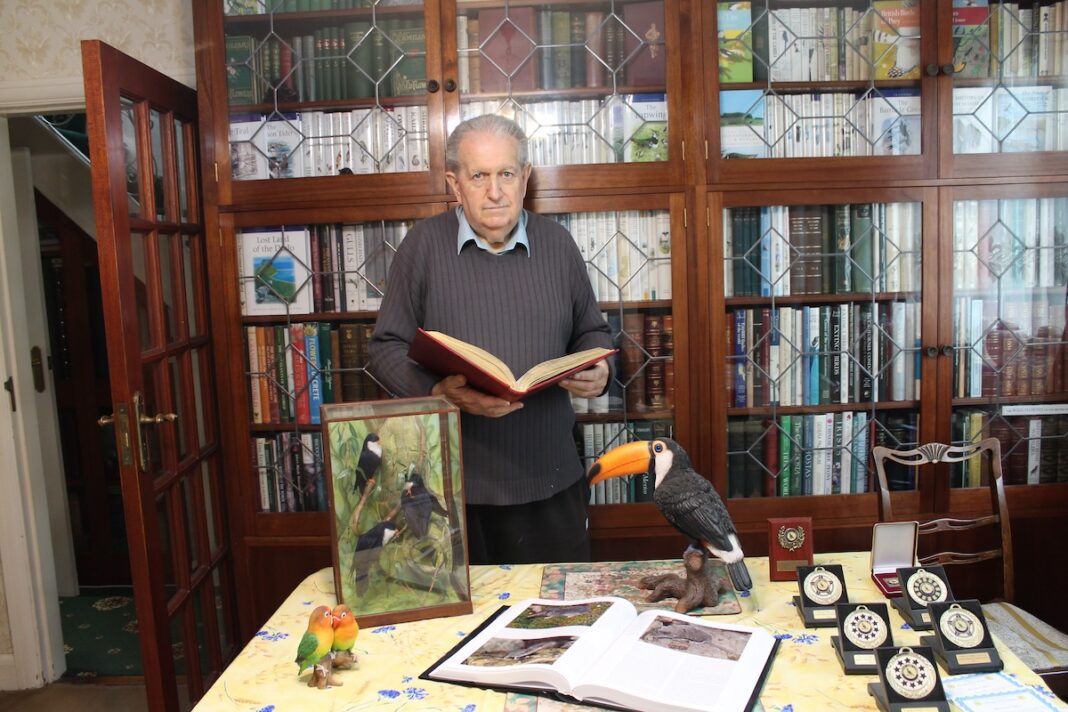

BERNARD Sayers, who has recently passed away aged 80, was an outstanding aviculturist. He was also a keen gardener, a lover of art – particularly relating to natural history – and a great collector of books, paintings and sculpture concerning the natural world.

Bernard wrote detailed accounts of his life as an aviculturist, which were published in the Avicultural Magazine. The first of these, “An Autobiographical Profile”, appeared in volume 111 (2005) and a five-part series “Fifty Years an Aviculturist” appeared between volumes 118 and 119 (2012-13).

Anyone wishing to read these articles, which profile many of the leading figures in British aviculture and their collections, can access them online through the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Bernard had an early love of natural history, fostered by growing up in the then semi-rural outskirts of Chelmsford, in a house backing on to farmland. As a small boy, Bernard helped the local dairy farmer feed his cattle and rode the milkman’s Suffolk Punch horses. Soon he began to acquire livestock of his own, initially common lizards and guinea pigs, but by his early teens he was breeding budgies and keeping an assortment of finches and other seed-eating birds.

Bernard regularly mentioned the lack of sympathy from his parents for his interest in birds. Nonetheless, they must have shown some tolerance (or acceptance), as by the time he was in his early twenties his collection included such diverse groups as hornbills, trumpeters, softbills, lories, pheasants and birds of prey, including at one time a king vulture (Sarcoramphus papa)! It was an extraordinary range of species to keep in a modest garden and by this time Bernard was working full time for the Marconi Co. in Chelmsford. Indeed, the 23-year-old Bernard was featured in Marconi’s house magazine under the title “Holy Hawks to Birdman” in 1967. The article mentions that Bernard had more than a hundred birds at that time and that he hoped to acquire a pair of keas (Nestor notabilis) later that year. Sadly, I don’t think that ever materialised.

A successful career

However the rigours of a responsible full-time job (Bernard rose from being a £3-a-week apprentice to management level at Marconi) meant that Bernard had to specialise in a narrower range of species. First, these were lories and lorikeets, but later owls: a group of birds with which Bernard had outstanding success. At one point, Bernard’s owl collection included most of the species available in aviculture. He himself imported a number of species into this country and achieved UK first breedings for eight species, including barred owl (Strix varia), chaco owl (S chacoensis) and southern boobook owl (Ninox boobook).

While on a business trip to Thailand, Bernard met a Thai lady, Nognut Promsawat (known to friends as Wattana), and after many obstacles put in their way by British officialdom Bernard and Wattana married. Wattana supported Bernard with his interest in birds and indeed helped him greatly with the maintenance of the bird collection and also tended the beautifully kept garden in Chelmsford.

Bernard worked for Marconi until retirement. Finding more time to spare, as well as acquiring some extra land due to a neighbour selling a plot, he again extended the range of birds he kept. Although owls formed the nucleus of the collection during the past two decades, Bernard kept such diverse species as striated caracaras (Phalcoboenus australis), Palawan peacock pheasants (Polyplectron napoleonis), king parakeets (Alisterus scapularis), rainbow lorikeets (Trichoglossus moluccanus), lemon doves (Columba larvata), curassows and a flock of Java sparrows. By the time Bernard ceased to keep birds, he had bred, during a 60-year avicultural career, more than 140 species. A true testament to his great skill as an aviculturist and one with total dedication to the birds in his care.

Further accomplishments

If Bernard had only kept birds, his achievements would have been considerable, but he was an outstanding collector of books, bird and natural history art, and birds’ eggs.

Bernard’s egg collection was unique and a remarkable achievement for one man to assemble. In the early 1970s, Colin Harrison, an ornithologist at the Natural History Museum and a fellow Avicultural Society Council member, mentioned to him that the national collection lacked the eggs of many birds that were then kept in captivity. Although these species had been imported and had often bred in captivity, their nests and consequently eggs had yet to be discovered in the wild state.

Bernard contacted fellow aviculturists, zoos and wildlife parks to request that the addled or infertile eggs of birds in their care be given to him to form a reference collection. Over the years, Bernard, later with Wattana’s help, blew thousands of eggs and eventually the collection was only second in number in the UK to that of the Natural History Museum at Tring.

Bernard hoped that the collection, all beautifully curated and in custom-built cabinets, would go to the Cambridge University Museum of Natural History and an agreement was formally drawn up for this to happen. However, a change in directorship of the Museum meant a change of policy and a collection of birds’ eggs was not a direction that the Museum wished to pursue. This upset Bernard hugely, as his oological collection was of great scientific importance and it should have been available to ornithologists as an important research source.

The collection is now in private hands and is unlikely to be available for scientific study in the immediate future.

Later life

Some years ago, Bernard was diagnosed with leukaemia. Nevertheless, although his illness curtailed some of his activities, he was still able to devote the required time each day to maintaining his bird collection. However, two years ago he decided that owing to further deterioration of his health he could no longer care for his birds to the standard he wished. The decision to part with the bird collection, although the correct one, affected him hugely. According to Wattana, he could no longer face going into the garden which was now devoid of birds and aviaries. Despite much suffering, Bernard bore his illness with great strength and fortitude.

The past two years were particularly difficult for Bernard and the deterioration of his health meant several stays in hospital, some lasting some weeks. At home he was cared for with great devotion by Wattana to the end.

Bernard’s fine natural history library is slowly being sold by an Essex auctioneer, Reeman Dansie of Colchester, and his treasured volumes, ranging from field guides to fine hand-coloured bird books, is reaching another generation of collector.

Conclusion

Bernard Sayers was one of the last generation of birdkeepers to have a connection with the rich age of private animal keeping between the Wars. He was young enough, when first keeping birds, seriously to have known the likes of Captain de Quincey, Terry Jones of the Spedan Lewis collection, John Yealland (one-time aviculturist to the Duke of Bedford and later curator of birds at London Zoo) and Jean Delacour, among others. Friends and acquaintances included Len Hill, Ken Dolton, Raymond Sawyer, Christopher Marler and Rosemary Low.

Personally I will miss my many visits to Chelmsford to see Bernard and to talk birds and bird books and to wander around the aviaries. He will be very much missed by many others, too.

Find more news and articles like this on the Cage & Aviary Birds website. Subscribe to Cage & Aviary Birds magazine now.